|

Peoples are moving quickly around the urban areas across the Earth. War, climate change and poverty are forcing people to leave our homes and move to safer places to live and raise our families.

In responding, the private sector is delivering goods and services. But it is not delivering communities. Governments are facilitating private sector responses, and not all are not safeguarding communities and ensuring future communities can flourish. Communities evolve. They grow among people with common background and common experience. They emerge, and dissipate. And they are necessary for our soul. Human settlements, their sustainability and the housing within them, combine communities. And women make communities as do men. Yet, in our haste to build new accommodation, are we making decisions that deprive women and our children of access to housing and to services? Where are the childcare services in the new apartment blocks? How can we raise babies in apartments with thin walls that require us to keep our babies quiet lest they disturb our neighbours? Why are places for children to explore the outdoors not prioritized in our urban designs? How can we afford to live in cities when costs are so high and everything: power, water, waste disposal, sanitation, transport; costs so much? Do urban planners unintentionally push women and children out of cities? Are women with children put on the waiting lists for community housing? Or is it easier to provide housing to older, single and active women? Are services to us our whole lives given priority? How can women and children access housing that meets children’s needs? How can we provide our children with opportunities to play and explore the world around us, to engage with nature? New York has built child-friendly areas into the design of its apartments. They have built in childcare and children activities to compensate for the loss of green space. They provide recreation for families and children. Livable cities are socially cohesive if they provide housing from early childcare through to old age. In designing our urban areas, we need to plan for people to live in their homes all their lives. Livable homes make for vibrant communities and safe spaces. For further information see the Habitat III Issues papers: 1. Social cohesion and equity: Livable Cities a. Inclusive Cities b. Migration and Refugees in Urban Areas c. Safer Cities d. Urban Culture and Design 2. Urban Frameworks a. Urban Rules and Legislation b. Urban Governance c. Municipal Finance 3. Spatial Development a. Urban and Spatial Planning and Design b. Urban Land c. Urban-Rural Linkages d. Public Space 4. Urban Economy a. Local Economic Development b. Jobs and Livelihoods c. Informal Sector 5. Urban Ecology and Sustainability a. Urban Resilience b. Urban Ecosystems and Resource Management c. Cities and Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management 6. Urban Housing and Basic Services. a. Urban Infrastructure and Basic Services, including Energy b. Transport and Mobility c. Housing d. Smart Cities e. Informal Settlements.

1 Comment

Kerry McGovern 15th March 2014

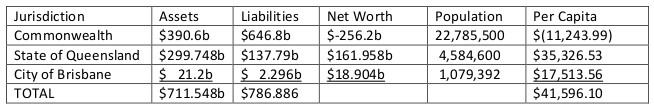

How much have you invested in Australia? How much do you, as a citizen of Australia, or your state and a resident in your local government own? What is it exactly that you are asking your elected members of Parliament to manage on your behalf? There are the services we use – public services for all of us. There are the private services the public sector contributes to making them affordable for all of us. And there is the stock of assets that our forebears have built for us, or we have inherited when we became citizens of this country. So what does citizenship and residency bestow on us? Collectively, we own and ask our representatives and the public service to manage on our behalf, the assets and liabilities that are recorded in the financial statements of our governments: The Commonwealth of Australia, The State of Queensland, and the City of Brisbane. Ever wondered what you, as a resident of Brisbane, living in Queensland and a citizen of Australia have a share in? First, let us get the mathematical and financial definitions out of the way. First, what exactly is one billion? It is a thousand million a billion, same as the Americans. It used to be a million, million, but the US dominance of financial markets means most countries now use 1,000 million to mean 1 billion. Second, what is the public sector? It consists of government departments, and agencies or statutory authorities, public non-financial corporations and public financial corporations and their controlled entities. The definition is the same all over the world as it accords with the General Finance Statistics, and the System of National Accounts published by the United Nations. So, given the financial statements of the Commonwealth, State of Queensland and Brisbane City Council report our total assets and liabilities, what do we own? Commonwealth The total assets of the Commonwealth, consolidated from all government departments and agencies funded from taxes, public non-financial corporations providing goods and services paid for by fees and charges, and all public financial institutions, including the Reserve Bank of Australia, were, as at 30 June 2012 $390.6b. Now assuming this value was still owned in September 2012, when the population estimates were released, each and every one of us: man, woman, child, and other residents own $17,142 in Commonwealth assets. $390,600,000,000 in assets and 22,785,500 people. Now, against that we have incurred liabilities: $646.8b. Now that is $(28,386) per person. So, each of us is in debt to someone or other at the Commonwealth level to the tune of $(11,244). Our Commonwealth Government appears not to be a going concern. Let us not pause there for long, but remember to carry forward a net burden on each of us of $(11,244). State of Queensland I also own a stake in the State of Queensland. The total assets of the State of Queensland, consolidated from all government departments and statutory authorities funded from Commonwealth payments and taxes, all public non-financial corporations and all public financial corporations, including Queensland Treasury Corporation, were, as at 30 June 2012, valued at: $299.748b. With a population of 4,584,600 that means each Queensland has a stake in $65,381.49 of public assets: Schools, hospitals, electricity generators, national parks, roads etc. Against these assets, we owe $137.79b or $(30,054.97) each. The means, we have a net worth invested in the Queensland State Sector of $35,326.52. Off-setting that against the Commonwealth negative net worth, it means we have a net investment in the Commonwealth and Queensland of $24,082.52 each. City of Brisbane And I live in Brisbane, so also have a share of its assets and liabilities. As at the 30 June 2012, the City of Brisbane assets were worth $21.2b. Our latest statistics for the population of Brisbane are as at 30 June 2011 when there were 1,079,392 people living within the City Council area. That means each of us owns $19,640.69 in assets. Against that were liabilities of $2.296b or we owe for our local government about $(2,127.12) each. That gives us a net investment, each, in the Brisbane City Council’s consolidated entity of $17,513.57 each. Consolidated Adding that investment to our net investment in the Commonwealth and State of Queensland of $24,082.52, we get a total investment in all our levels of government, each, of $41,596.10. Total Investment in the public sector of Australia per capita is $41,596.10. If you live with a partner, and have two children living at home, then your household has an investment of $166,384.40. And that is the same regardless of your individual wealth or status. Each of us, by dint of being born in Australia, or being accepted as residents of Australia, is responsible for collectively managing a total asset base of $711.548b. Assets and Liabilities are spread differently with more people to carry the Commonwealth’s net loss than the Brisbane City Council’s net worth.  Jane Stanley is director of FOCUS Pty Ltd, an international consultancy with a commitment to working with rural communities and supporting regional economic development. Jane has previously worked as an adjunct professor at the Australian National University, and she has served on the executive of a number of professional peak bodies and ministerial advisory committees. Currently she is vice president of the Australian Chapter of the Eastern Regional Organisation for Planning and Human Settlements (EAROPH), an Asia-Pacific peak body affiliated with UN Habitat. Jane has undertaken numerous property planning, business planning and advocacy projects with farming groups in Australia and overseas, including her recent pro bono work for Farmer Power Milk: cheaper than water. Photograph: Dave Thompson/PA What is wrong with this picture? Domestic and international demand for dairy produce is booming, but the price of Australian milk has declined so far that it is now cheaper than water. The dairy industry has been deregulated, but our dairy farmers don’t benefit from rising prices. Instead of being protected through tariffs, farmers are now prevented by regulation from selling directly to consumers, and they can face substantial penalty payments if they change the milk factory they do business with. On top of this, all dairy farmers have to pay a levy to run the national industry body, Dairy Australia. They can’t opt out of this as it is taken out of their milk cheques by the milk processors. Last year, the levy on farmers raised over $30m – amounting to about $7,000 for the average farmer. Many would argue that the main beneficiaries of Dairy Australia’s activities are the dairy processors (who actually control the selection of board members), while they make no financial contribution at all. The government contributes around $19m per year, and you would have thought that this might have led to significant questions about value for money – amounting to over half a billion dollars over the past 10 years. Similar criticisms are made by farmers about their state representative bodies, which are funded through yet another levy (another $2,000 or so). These bodies have recently bought into arguments about corporate takeovers without consulting their members, seemingly in conflict with farmers’ interests. That contribution of $9,000 for the average farm particularly hurts when viewed against declining farm incomes. As milk prices have been forced down, many farmers have had to borrow against the equity of their farms, but often without sufficient income to meet their repayment obligations. As farm values and incomes have fallen, the banks have tightened the screws. Many farming families are now unable to pay for hired help, so that young and old farming men and women are putting in 16 hour days and still do not make ends meet. A young child holds up a sign along with hundreds of Tasmanian dairymen in a 2009 mobile protest against milk price cuts. Photograph: /AAP/Dale CummingIn South West Victoria, which produces about a quarter of Australia’s milk, net farm incomes fell from over $195,000 per year in 2010-11 to just over $51,000 in 2012/13, with 21% of farms running at an absolute loss (negative cash flow). Over half of all dairy farmers have increased their borrowings or deferred debt repayments over the past year to cope with this crisis. Industry confidence has plummeted, and in some regions as many as 30% of farmers expect to have quit farming within the next five years. This is not surprising, as one piece of independent research concluded that on present trends, the average net farm income in 2017 would be zero. Not surprisingly, milk production is falling as farmers cull their herds, sell their farms (sometimes handing the keys to the bank) or tragically take their own lives. Milk processors are already experiencing shortages of supply, and this situation can be expected to worsen. However, even this isn’t leading to an increase in the farmgate price, with processors being locked into long term contracts for cheap milk. Low domestic prices are driving up demand for fresh milk but there is no supply to satisfy it, meaning that even less is available for export. What a contrast with the situation in New Zealand – their farmers receive around 50% more per litre for their milk, in an environment with much lower production costs. Milk production has doubled there over the past 10 years, with the result that the lucrative export markets in Asia are being gobbled up by the New Zealanders, while Australia is being left out in the cold. You would have thought that the government would be concerned about this. However if you look at the industry reports prepared by Dairy Australia and others, you would get the impression that everything was rosy. There are volumes written about how tinkering at the edges can slightly increase production efficiency, but almost nothing about how to resolve the main problem of farmgate price. Farmers are gobsmacked by the seeming ignorance of their plight, and the fact that industry stakeholders have forgotten that milk actually comes from cows. Many of the industry reports assume that as farmers quit the industry, farms will simply consolidate and become more efficient. Ask the cows about this – a heavily laden Daisy the cow might have to double the distance she walks to get milked twice a day, impacting on both her milk yield and her productive life. Ask the family farmers who see the amalgamated corporate farm next door go bust, with the fields left abandoned. And ask the farmers about how things got so bad. Most of the blame is put on the farmgate price, which is now about 50% lower than that needed to make dairy farming profitable. Farmers’ anger is well demonstrated by the several hundred people turning up at Farmer Power meetings held to air their concerns – and at the mental health workshops convened to help them deal with their stress. There has even been some discussion about withdrawing from membership of the various industry groups in protest at the lack of action, even if they can’t withhold the compulsory levy. Farmer Power has a clear mandate from the dairy farmers attending its meetings to lobby for substantial change in the way the industry is managed. Their concerns include the need to review the way that the various industry bodies do or do not serve farmers’ interests, and an investigation into the other restrictive practices that are crippling their end of the food chain. It is calling on the new minister for agriculture Barnaby Joyce to require a fully independent review of Dairy Australia and the state industry bodies to ensure that both farmers and tax payers receive good value for their substantial investments. Farmer Power is also calling for a review into the full range of restrictive practices within the dairy industry that are hurting our dairy farmers. Published in The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/dec/17/milk-is-now-cheaper-than-water-dairy-farmers-deserve-better South Africa offers a tremendously exciting environment for discussion of ideas, and innovation in urban development. The “new” South Africa has huge challenges for creating satisfactory living environments for millions of its black citizens who were/are living in slums. There is some highly creative thinking going into spatial design, building construction, tenure arrangements and finance. There is an influx of skilled professionals from a variety of countries and cultures to add to this creativity. This includes a significant contingent from Holland, where there is some particularly innovative professional thinking around Open Building techniques (see below) and social housing best practice.

The first of these conferences was a cross-disciplinary forum, with good representation from all levels of government, social housing providers and the development industry. I provided a 20 minute workshop presentation on Community Engagement, which was well received. The other presentations included a New Zealand paper about transformation of a large public housing estate using a community based model. There was some reporting back from the recent World Urban Forum held in Naples, with a significant finding being that there was a disturbing observation about increasing social distance between people making policy and those experiencing the impacts of policy implementation, at all levels of government including local government (which made my paper all the more significant). However the main value of attending this conference was to absorb current thinking about housing and thus put on my housing brain, which helped me to draft a Discussion Paper as a prelude to a Housing Policy for the City of Ballarat. The second conference was organised by the South African Architects Institute, and was more focused on best practice housing and neighbourhood design. I was given the opening keynote address for which an hour was allowed, and I customised this around some issues I had been briefed on that were of particular local relevance. These included mobilising the community sector for mass urban transformation (experience from Glasgow UK) and development of tri-sector partnerships for significant urban reform (experience from international development projects), which I had been asked to talk about. Three other international experts had been invited to address the conference on various aspects of Open Building and System Separation, which are emerging areas of innovation in Holland, the USA and some other western countries. These concepts have particular relevance for South Africa as well as for Australia/Ballarat, as outlined in the following summary. Open Building, System Separation and Sustainable Asset Management An architectural concept of “Supports” was developed by Dutch architect John Harbraken in the 1960s, and was inspirational when I was an architectural student. This involves design of built frameworks using modules (he used the dimensions of a traditional Japanese floor mat) within which users could slot in customised modules, with the capacity to adapt buildings over time. This concept was used in the construction of the iconic “Habitat” building that was showcased in Expo 1999 in Montreal (which I also travelled to see). Harbraken’s concepts have recently received new momentum with the development of the Open Building concept in the United States and Holland, apparently inspired by Harbraken’s original work but taking it much further. In Open Building the emphasis is on design of the primary structure, which has inbuilt flexibility to provide for immediate customisation as well as future adaptation. It can be applied to new building or renovation of existing buildings, small and large. There are increasing numbers of Open Building practitioners, with particular application to residential buildings and health care structures (the latter because of the rapid obsolescence of any fully developed design solutions, and the need to accommodate as yet unforeseen medical developments, with regular refurbishment). Systems Separation is a practice that has been developed in parallel with Open Building, and the two are now being linked. In Systems Separation the usual phases of a building’s construction are completely disconnected. Design and construction of the primary structure is commissioned as an entity in its own right, with the brief providing for a high level of durability as well as flexibility. The secondary phase of a building’s completion (interior design, completion of aesthetic treatments) is commissioned as a next phase, at the appropriate time. The tertiary phase (equipment and furnishing, building commissioning) may be pursued in stages once the appropriate configurations are clear. It is claimed that this separation is cost effective and provides much improved results, because the skill sets required for the three stages are quite different (an analogy was made between tennis, badminton and ping pong). Separation also provides for changes to be made along the way, as well as design for future uncertainty. This provides primary building solutions that are highly sustainable, because of their immediate and future adaptability. There is an obvious link to be made between these two concepts and with emerging best practices in Sustainable Asset Management, which professional bodies such as EAROPH are leading. All three concepts suggest a need to shift from a focus on the initial construction of a building to considering (and lengthening) its life cycle. An analogy that I can make is derived from the book “Factor Four” (Amory Lovins et al) which urges halving inputs and doubling outputs to improve sustainability. One of the many case studies in this book relates to a carpeting company which original defined its business as “selling carpets”. After some clever Factor 4 thinking, it redefined its business as “keeping floors carpeted”. It focused on producing and laying carpet tiles, and there was an annual inspection to replace any worn tiles, these then being recycled to produce new tiles. Far fewer tiles were produced in total but floor were better carpeted at all times, more people were employed and profitability was much improved. The analogy with buildings is clear to me. If we are to achieve sustainable buildings we need to switch from a focus on the initial construction to an annual investment, maintaining the value and functionality of the built assets, and adapting the secondary and tertiary systems on a regular basis to adjust to the changing needs of users. There are many disincentives for making this switch, especially in an environment where external funding is only available for capital projects at the initial construction phase. However if the initial investment can be made in maximising the durability and flexibility of the primary structure, this may facilitate a more cost effective ongoing process of annual investment in cyclical maintenance as well as adaptation to changing use patterns. Some of the leading proponents of Open Building and System Separation are keen advocates of design competitions as a way of encouraging innovative solutions to the design of the primary structure. Because a high level of flexibility and adaptability is required, the conceptual development can be carried out remotely from the social context, and possibly from the details of the physical site (depending on the site constraints and opportunities and the level of information that can be provided). Given the highly innovative nature of these concepts in Australia, it is possible that State or Commonwealth Government support could be secured for these competitions (and perhaps for implementation). System Separation guru Georgio Macchi, who has been responsible for major urban developments in Switzerland, indicated to me that he would be willing to help with this, and offered himself as a design panel judge. There was also enthusiastic support from US Professor Stephen Kendall, who is an Open Building advocate. There are three possible applications of these concepts to Ballarat that are apparent to me, and which might be considered as possible project initiatives. All could be the subject of design competition. 1. Civic Hall. It seems to me that System Separation would be highly appropriate, and that the nature of the building makes it very suitable as the subject for a design competition. A robust and adaptable primary structure could provide flexibility for a variety of as yet uncertain uses to be introduced, and for these to change over time. 2. Indoor sports buildings. Constructing these is a significant investment, and there are challenges for sustainable asset management, providing flexible multi-use spaces, and allowing for adaptability over time. It is planned to convene a futurist workshop on the possible ways that sport and recreation patterns will change in Ballarat over the next 20-50 years, and this could generate the brief for an innovative generic Open Building design. 3. Demonstration housing project. One proposal emerging from the recent housing workshop in Ballarat is establishment of a consortium to develop innovative small dwellings that can fill a market gap and demonstrate good practice to the development industry. Open Building can provide an exciting framework for small dwellings, allowing for customisation of spaces to meet the needs of the initial occupants, but providing flexibility for structures to adapt to the changing needs of these people or other occupants. It is possible that some private sector sponsorship (peak industry or professional bodies) as well as government support for an initial design competition around this concept could be encouraged. As another follow on from the South African conference, I have been encouraged to engage with EAROPH in linking best practice Sustainable Asset Management modelling to the Open Building and System Separation conceptual development (which has its own financial modelling templates). An appropriate vehicle for some global collaboration on this new thinking woutl be through the International Federation of Housing and Planning, which partners with EAROPH but is based in Amsterdam. Professor Kendall is particularly keen that this should be pursued. If the City of Ballarat would like to play an active part in this global discourse, it would be an easy step for it to become an EAROPH corporate member. Dr. Jane Stanley EAROPH Australia Executive Committee Member Director for People and Communities for Ballarat, Ballarat City Council |

Archives

September 2015

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed